“Following every great bubble the senior currency eventually became ‘chronically’ strong relative to most asset classes, including commodities, and other currencies for most of the time.”

– Bob Hoye, chief strategist of Institutional Advisors

***

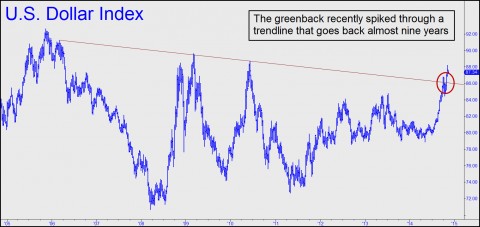

With the U.S. dollar in the throes of a rally that has been rampaging since June, it’s time to revisit an idea that I first wrote about nearly twenty years ago – that a short-squeeze on the dollar could eventually cause a meltdown of the global financial system. Although doomsdayers have put forth many theories about how economic Armageddon might play out, it was always a given that the dollar would be at the very center of the crisis. The reason for this is that there are vastly more dollars in play globally than the central banks, even acting in concert, could hope to manage when the day of reckoning arrives, as it most surely will. There are perhaps a quadrillion digital dollars swirling in the financial ether right now, most of them created not by the central banks, but by modern-day alchemists who have transformed the very flotsam of the securities world – Bolivian reverse floaters, non-performing receivables of all kinds, rehypothecated brokerage accounts and such — into seven- and eight-figure bonuses for every partner on Wall Street. Each and every one of those dollars represents both an asset and a liability on the macro ledger, and although they would cancel each other out at some level, it can hardly be assumed that this would occur in an orderly way, if at all, in the event of a financial panic.

That the preponderance of those quadrillion dollars are being used to sustain an epic financial Ponzi scheme is inarguable, since the output of real goods and services in this world amounts to no more than around $80 trillion. The huge excess of funny money is tied mainly to debt instruments with life spans measured not in months or years, but in days or weeks. At present, the market for these instruments continues to function smoothly. This is mainly because a U.S. stock market trading at record highs has provided a psychological barrier against fear. However, if some unforeseeable event were to disrupt normal loan settlements, short-term borrowers unable to roll their debts would be pressed hard to settle up in cash. Given the sums involved, this would be like trying to evacuate Manhattan via the Holland Tunnel in an hour. As a result, the banking system would lock up overnight, triggering branch closures that could last for weeks or longer. The Fed would be powerless to act, since the fragile trust that currently allows the banksters’ to ply their Ponzi scheme will have been irretrievably lost. Cash would be in ruinously short supply, credit cards would no longer be accepted by anyone, and the economic world would be pushed into a state of barter. For anyone holding actual currency, fives, tens and twenties would be the coin of the realm, since that’s the only kind of money sellers of food, gas and emergency supplies would recognize at that point.

“Are You Nuts?”

When I ran this scenario past a few international finance professors some years ago, they acted like I was nuts. Even the authors of The Incredible Eurodollar, the book that had led me to believe that a short-squeeze on the dollar was possible, averred only that the theory sounded “interesting.” From a deflationist perspective, however, a panic-driven scramble for dollars seems not merely plausible, but likely.

For readers unfamiliar with the concept of a short squeeze, a brief explanation is in order. A short squeeze can occur when it comes time to repay a loan in some good or medium of value that has been overborrowed. If, in the interim, the supply of the good or medium has been reduced or curtailed for some reason, the borrower might have to pay up for it to acquire it for delivery. This happens all the time in the stock market. Speculators bet against companies by shorting a company’s shares in expectation of replacing them at a lower cost. They have effectively sold shares that exist only in virtual form outside of the float, and if there’s a dividend to be paid, the short seller must pay it out-of-pocket. If the stock price falls, the short sale will be profitable; but if the price rises, short sellers will be on the hook to deliver at the original price. A contractual seller of nearly any item could conceivably be caught in such a bind. Consider the builder who promises in writing to complete a home for $1.25 million that includes copper roofing and gutters. If the price of copper were to rise by a significant amount, the extra cost to the builder might wipe out his profit or even produce a loss.

Subprimes Are Back!

To put this in the context of the dollar, all who owe have effectively taken short positions against the dollar. As such, they are implicitly rooting for inflation, since it will allow them to retire the debt in cheapened dollars. That’s a very big bet in the aggregate, since it encompasses all mortgage debt. Unfortunately, the opposite holds true for borrowers right now. Deflation has begun to overwhelm the expansionary goals of monetary easing, particularly in Europe. Meanwhile, the dollar is becoming dearer by the day despite the Fed’s best efforts to keep it in plentiful supply. And although inflation is obviously rampant in the stock market, it no longer obtains in the housing sector. Nor will it return any time soon, judging from the Fed’s wantonly desperate attempt to power real estate inflation with a new gusher of subprime loans and 3% downpayments from those who could not otherwise afford homes.

So far, the rise in the dollar seems benign, even if it has begun to negatively impact overseas earnings of U.S. multinationals. But if the dollar continues to move higher, you can be certain this will unsettle the arrangements that have swelled the derivatives bubble to its current size. More to the point, a steepening or even parabolic rise in the dollar would begin to suck money out of all investments and into the presumptive safety of Treasury paper. Thus would the world’s investment capital come to reside in securities yielding 2.5% (and falling), sending all other classes of investable assets into a tailspin. That would be debt deflation at its worst and most unstoppable. With real estate prices falling more steeply than during the financial crash of 2007-08, even 3% mortgages would become a crushing burden on homeowners.

Against this outcome, we can only pray that the dollar stops rising. However, on the basis of the foregoing we already know why this is occurring, and so we shouldn’t get our hopes too high. In the meantime, the old adage applies: He who panics first panics best. That means leaping into long-term Treasurys right now with abandon, before most investors begin to figure out that the already impressive bull market in U.S. debt has been merely a warm-up. For a detailed commentary on this that appeared on Rick’s Picks a month ago, click here: Inflation, Deflation and Our Very Confident Bet in T-Bonds.

With all the thoughtful comments, above, I’ve only seen Mava, thank you, draw the conclusion that I hope would be addressed, that is, the federal government can expand its give-away programs to people-people and corporate-people, ala a million dollars in every pot, except in the greedy .1% ers’ $1, 000 pots.

I understand Rick’s points about the increasing ineffectiveness of expanding GDP per dollar of addition debt. Since when, lately, has the Gov’t been concerned about inefficiency?

If you give individuals the money to pay off their mortgages, there won’t be a mortgage crisis. The homeowner is happy (as Rick noted, above), and the lender is happy.

I never thought that the government and central banks could save the financial world in 2008-2009. They did it with, relative to the GDP, a minor increase in their balance sheets. Why can’t they save the world again? Yes, the percentage increases in the balance sheets look dramatic, but a doubling or tripling from here doesn’t compare to the US or world GDP.

Rick, thanks for the forum.