[The weekly column I freelanced to the Sunday San Francisco Examiner in the late 1990s was as relentlessly bearish as my Rick’s Picks commentaries are today. However, the essay below, published in 1997, was a notable exception. Its thesis was that U.S. companies both large and small were perfectly positioned to benefit from the emergence of a global middle class. Alas, America’s manufacturing sector instead moved offshore even as our multinational banks bulked up massively on steroids. We now know that the world had no need whatsoever for a ‘financial superpower’; rather, what it does need, and thrives on, are the tangible goods and real wealth created by such emerging economic superpowers as China, Brazil and India. We can only hope that when the U.S. banks’ inevitable steroid breakdown has run its course, the U.S. will return to making money the old fashioned way. RA]

U.S. stocks have been in a scorching, vertical climb for months, confounding the bears and effortlessly vaulting the immediate expectations of the most ardent bulls. What factors might they have overlooked in gauging the market? Could there be forces at work more powerful than the steady earnings growth and low inflation usually cited as key reasons for the longevity of this bull cycle, now well into its seventh year? I believe so. A more plausible explanation may lie in the relatively recent and rapid emergence of a vast, global middle class, particularly in Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America. To the extent this trend creates a burgeoning new marketplace for a wide variety of goods and services, U.S. companies stand to benefit the most, since they are indisputably the best in the world at meeting its demands.

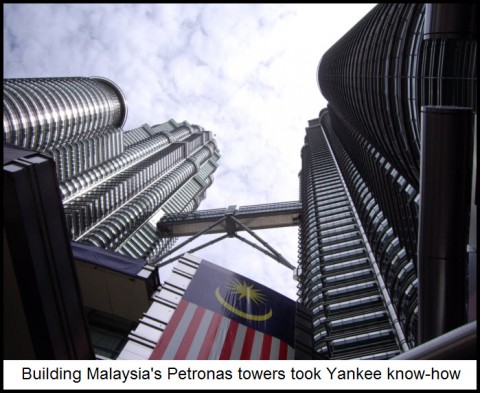

The point was driven home to me recently by news reports that the Malaysian government, with public and private outlays of as much as $15 billion, will attempt to replicate the Silicon Valley in the rolling countryside just south of its capital, Kuala Lumpur. The intention is not merely to create some industrial-park-on-steroids where workers can have a crack at the minimum wage by churning out trinkets for export. Rather, it is an all-out effort to catapult Malaysia into the information age, thereby allowing its labor force to compete on an equal footing with some of the highest-paid workers in the world – most notably, the software engineers, chip designers and networks specialists of Silicon Valley. It is a fantastic undertaking: creating a Buck Rogers city-within-a-city on land that is now producing little besides palm oil. But within 10 years, the tract dubbed the “Multimedia Super Corridor” could easily become the most technologically advanced urban enterprise zone in the world, with schools, hospitals, government and retailers patched into a $2 billion network of fiber-optic cable. There will also be a Multimedia University to serve as an intellectual breeder-reactor, much like Stanford.

Malaysian Corridor

As the corridor develops – and in the space of a single generation – per capita income is expected to quadruple from its present $4,500. Simultaneously, Malaysia would presumably emerge as a global purveyor of computer hardware, software and high-tech services. To the extent this occurs, incomes in this part of the world, as well as elsewhere, are about to take off on a runway paved by Yankee know-how. The implications for U.S. multinationals are positive, to say the least, and may serve to explain why the U.S. bull market is not as mature as some would speculate.

It is not just the shares of Fortune 500 giants like Pepsi and McDonald’s that we can expect to benefit, either. Indeed, dozens of smaller companies, some publicly listed, played a key role in the construction of the world’s tallest building, the Petronas towers in Kuala Lumpur. U.S. firms did the architectural work, installed the glass, and even helped local contractors circumvent prohibitive tariffs on structural steel by developing a type of concrete four times stronger than anything ever poured in Malaysia. If Malaysia were the only country gearing up like this, it would surely be good news for the shares of U.S. companies with global reach, not to mention their domestic suppliers.

But the fact is, similar leaps are taking place all over Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe. No longer does it require the span of a generation for a middle class to evolve in places previously regarded as economic backwaters. Any country with sufficient brain power, private property and stable government can leapfrog the blue-collar stage of industrial development. This lends immediacy to a question that Wall Street has always pondered wistfully: What if we could sell a single widget to each and every household in China?

***

Click here for a free trial subscription that includes not only access to two 24/7 chat rooms that draw veteran traders from around the world, but also real-time trading alerts via e-mail.

Agree.

The thing is, we all consistently lay-off Americans whenever we buy something made by foreigners. But, no one likes to think of it this way.

My favorite shpiel to some of these overly-fervent “patriots” is always this: “So, no more Samsung TV for you, I understand? Down with Sony and on with Sceptre?”