A story last week in the Wall Street Journal provided a fascinating glimpse into the world of high-speed, or “algo,” trading. Who knew there was something called a “Hide Not Slide” order lurking in the murky shadows of electronic trading? Although this particular type of transaction might be difficult for the layman to understand, suffice it to say that it electronically hides or exposes bids and offers as needed with the skill of a three-card Monte hustler. The regulators supposedly are looking into algo trading because they suspect it might enable some traders to take unfair advantage of others. That would be putting it charitably – so much so that it is predictable that the SEC will detect a stench wherever they poke their noses, since it’ll be like sniffing out political corruption in Chicago during the Roaring Twenties. In the meantime, the Journal’s report on the probe in its early stages turned up stories that verged on the lurid, including one about a firm that advertised itself as a haven for big investors worried about getting picked off by algo traders. Turns out the firm, Pipeline Trading Systems, had an algo operation of its own called Milstream.

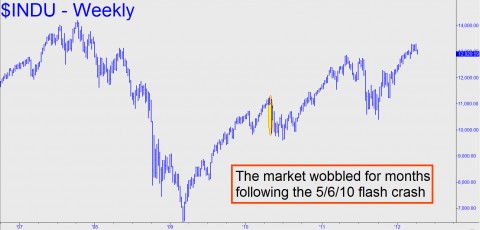

More than being merely suspicious about the way today’s electronic markets work is the BBC’s Max Keiser, a world-class muckraker who can smell financial scat a mile away. In an interview we did with Max on Monday that will be linked here later this week, the discussion concerned some of the ways in which technological wizardry has helped tilt the playing field in favor of the trading world’s “one percent” elite. It may also turn out to have destabilized the markets so that a global flash crash is possible. We said as much in a recent commentary, and that is what drew Max’s attention. Do we actually believe this? You bet. But even if we’re wrong, algorithm-driven trading has most surely supplanted what vestigial integrity remained in the game during the 1980s, when we worked as a market maker on the floor of the Pacific Coast Exchange. Traders shouted in each other’s faces and used hand signals to effect transactions in an “open outcry” system little changed from the open-air auctions held hundreds of years earlier beneath a buttonwood tree at the foot of Wall Street. It wasn’t until the 1990s that rocket scientists took over the game. Writing for Barron’s in 1995, we lamented the change in an essay, The Way It Was, that described how the sun had set on options-trading cowboys. The cowboys of the financial district may have represented a horrendous bottleneck in the world of globally networked trading, but it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that the game was more honest when humans still came face to face to trade in securities.

(If you’d like to have these commentaries delivered free each day to your e-mail box, click here.)

Rick: Camouflage trading, taught as part of the Hidden Pivot Course, puts us right on top of the lesser charts. I’ll let those who have taken the course vouch for my claim that it is easy to beat the machines. If anyone can devise a Trader vs. Deep Blue competition, I would welcome the chance to prove my point. RA

—————————————————————–

See my note above. Computers may beat the very best chess players, but I don’t think they can outwit a good technical trader. RA

You seem to be contradicting your own thesis but you’re supporting mine.