[Statistically speaking, the average Baby Boomer has not socked away nearly enough to live well in retirement. Is there time to get back on track? Yes, according to our good friend Doug Behnfield, a Boulder-based financial advisor. But it won’t be easy, he says, and the steps he has outlined below in a letter to clients will create a heavy drag on the U.S. economy in the years ahead — especially if millions of Baby Boomers try to play catch-up by saving like crazy. RA]

When I turned 55 years old back in 2009, I did a study to determine what the 80th percentile 55-year-old household looked like financially, in general terms. I originally called the EBRI (Employee Benefit Research Institute) in Washington D.C. because I wanted to get a feel for how well prepared my cohort was for retirement. I was referred to an economist at the University of Chicago who heads up the Survey of Consumer Finances for the Federal Reserve Board. Not exactly the beginning of a movie script, but I struck up a very informative relationship with this individual who lived and breathed the financial reality of the American household.

What unfolded was an eye-opening effort to determine what it would take for the Baby Boomers to retire with a lifestyle befitting the upper middle class of one of the most prosperous societies in the history. After all, who could be so pessimistic as to forecast failure for the people who sit at the center of our most influential demographic age group? But the data on their current financial condition is, to say the least, daunting. And particularly now, at 57, they do not have much time to prepare.

There were three primary reasons why I chose the 80th percentile 55 (now 57) -year-old household. First, people in the 80th percentile have the wherewithal to change their behavior to adapt to changing financial goals. Second, I am 57 and was curious about who I was hanging out with. Finally, the people born in 1954 are practically at the center of the Baby Boom, which is defined as those born between 1946 and 1964.

$100,000 in the Hole

The 80th percentile, 57-year-old’s household income is little changed from two years ago (or four years ago, for that matter) and stands at $150,000. They have, on average, a $200,000 mortgage on a home valued in the low $300,000s. (The value was $370,000 in 2007). If they have a 401K or IRA, the balance is approximately $100,000. Other assets and liabilities are very difficult to generalize and quantify. The quantity and frequency of debt beyond a first mortgage is significant and so are non-retirement-plan financial assets, but they appear to generally offset each other. It is safe to say that if you Google Earthed the $315,000 neighborhood in Columbus, Ohio and pulled out the 57-year-old’s household, you might find that their home equity loans, education loans and auto loans offset their financial assets excluding home and retirement accounts. If that were the case, they are $100,000 in the hole with eight years to go to retirement.

There are many reasons why the Baby Boomer is generally underfunded actuarially for retirement, but the two most important ones are: 1) a cultural aversion to saving organically and 2) extremely poor investment performance during the last decade. (You haul sixteen tons and what do get? Another day older and deeper in debt.)

Consider that at the tail end of the 1980s, when today’s 57-year-olds were about 35, corporate defined benefit pension plans were largely frozen and employees were transitioned to self directed 401K plans in which the rank and file had to choose the amount that was deducted from their wages to fund their retirement account. They were also given discretion over the asset allocation in the account. They reached the age of 46 when the stock market peaked in 2000 and 52 when the real estate market peaked in 2006. Since 1999, the S&P 500 Index is flat, but there have been two 50% decline phases and numerous leadership changes. In general, the public has been put through a meat grinder in the stock market for the last 12 years. Poor performance in retirement savings contributed to the enthusiasm for real estate investment that began after the Savings and Loan Crisis in the mid 1990s but accelerated into a debt-fueled mania starting in 2002. By 2007, most Baby Boomers counted their real estate holdings as a primary retirement investment. We are talking about their home and perhaps a vacation property. By now we all understand that humans are prone to crowd behavior but Mother Nature is a hanging judge.

Declining Yields

To make matters worse, interest rates, and therefore the yield offered by conventional fixed income retirement vehicles (i.e. bonds) have been declining since 1981, when most 57-year-olds were buying their first refrigerator. Thankfully, the core rate of consumer price inflation has been coming down in lock-step, but still, the market is not generous in the way of guaranteed cash flow on retirement savings.

Returning to my mission: How could the upper middle class Baby Boomer retire with dignity, given their dramatic level of underfunding? There is a bit of a planning debate about what the level of retirement income should be relative to pre-retirement earnings. In addition, opinions vary on what an appropriate distribution rate is on retirement savings, based on a deep desire not to outlive one’s nest egg. Generally speaking, it is not more expensive to go to work than it is to lead a retired life, so the appropriate level of retirement income should probably be roughly equal to pre-retirement spending, or higher. A 4% distribution rate on savings is considered a conservative standard for those retiring at age 65, due to the annuity calculations that apply to that pesky part about not running out of money. The percentage is lower for early retirees and higher for those who postpone retirement. (That is why Social Security benefits are higher for those who delay the start of payments past the “normal” retirement age.) Based on a conventional approach, these 57-year-olds need to accumulate about $3 million in retirement savings in the next 8 years in order keep everyone happy. That figure is based on the calculation that they need to replace $150,000 per year in employment income when they quit working and they will receive about $30,000 in Social Security, leaving a $120,000 funding gap. It takes $3 million to fill the gap at a 4% distribution rate. Because saving $3 million in eight years is absurd for this group who has spent practically every after-tax dollar they make, dramatic behavioral change seems to be an easy prediction. And the changes will have an enormous impact on where the global economy is headed for the next decade because, remember, there is a large Baby Boomer cohort in all the developed countries, not just the U.S.

I came up with three primary actions that can be taken in order for these 57-year-olds to retire comfortably, if taken together. All of them will have a potentially negative impact on the economy: 1) postpone retirement to age 70 or older; 2) cut the household budget and save the difference, and 3) liquidate debt by downsizing. Now, that seems simple enough, but there are a lot of moving parts. The big question is: Will they do it, or will they end up living in their kids’ basement? I am optimistic. But keep in mind that these three actions, if they become the fashion, will depress the economy. Postponing retirement has a negative impact on the employment outlook because they will not be making way for younger workers. If a cohort that large decides to take the knife to the household budget, we get the “Paradox of Thrift”. What is good for the individual household can lead to lower economic activity for the entire society. Likewise, everyone cannot put a sign on the lawn at the same time without putting enormous pressure on prices. But in a somewhat idealized approach, here is how it could play out:

Postpone Retirement

By postponing retirement to age 70, the time allowed to prepare is increased by more than 50%. Social Security payments probably increase to $35,000. In addition, the distribution rate on savings can be increased to 5% or 5 ½% because of the shortened duration of retirement. At 5 ½%, it only takes $2,091,000 in savings to generate the additional $115,000 in annual retirement income. Now we are getting somewhere! But $2 million in savings is still out of the question, even in 13 years.

Cut Spending, Increase Savings

In order to get to age 57 with mortgage and consumer debt that exceeds retirement account balances, the unfortunate conclusion is that with this cohort, saving has not been in fashion. That will have to change. For example, $150,000 in household income yields approximately $115,000 in after-tax income, and that is what they have been spending. Yes, they put $10,000 or $15,000 into their 401K each year, but they also borrow to buy a car or remodel the kitchen every few years for 30 grand, so the net savings has been minimal. They need to take the $115,000 in spending down to, say, $75,000. Talk about choking the horse. But it certainly can be done. That will facilitate $40,000 in annual savings, but what is really cool is that, after adapting to the pain of austerity and establishing a less expensive lifestyle, the savings goal drops to $1,080,000! That is because it only takes $95,000 in taxable income to net $75,000 in spendable income and since the Social Security benefit is close to $35,000 if you wait until age 70 to start drawing, that leaves just $60,000 in income to fund through savings. $1,080,000X 5 ½%=$60,000. Wow! But saving over $1 million in 13 years takes more than $40,000 per year unless the returns are in the high double digits along the way. It is unlikely that high investment returns will be achieved in the environment that we are creating with this type of household behavior, so one more action must be taken.

Downsize, Liquidate Debt

One thing that the upper middle class had in common as the old paradigm achieved its secular inflection point in the last decade was that they maximized their real estate portfolio. That typically involved movin’ on up to the best neighborhood they could qualify for and/or picking up a condo in the mountains, a shack on the beach or cabin at the lake. The beauty of investing (i.e. speculating) in personal residential real estate was that you could dramatically enhance your quality of life while getting rich at the same time. In reality, it was an epic debt-fueled investment mania.

The rationale for the vacation property investment was that you could achieve price appreciation while enjoying the warmth and camaraderie of your very own retreat. If you were able to rent the place and generate some revenue, that was icing on the cake. But priorities are changing. Enthusiasm for escape is waning as everyone struggles to adapt to a new paradigm of frugality. Price appreciation appears to have morphed into a depreciating trend. The revenue-generating capability is woefully inadequate in relation to the original expectations.

The main house is a ball and chain too. With four bedrooms on a half acre, it is hard to match square footage with an empty-nester lifestyle. How often do the kids show up, strike up a game of touch football and spend the night? The 2 or 3 bedroom patio home in a walkable location probably makes much more sense. One weird thing is that our children, now in their late 20s and early 30s, are trying to rent the same property. Never the less, by dumping the old paradigm real estate and buying into an efficient, stylish (and less expensive) abode, you could dramatically cut your household budget.

Real Estate ‘Crucial’

The real estate decisions are critically important because such a large percentage of the household budget goes to housing. Because expectations were so irrationally elevated during the bubble, abandonment of the real estate investment thesis is proportionately difficult. Achieving the necessary level of retirement savings requires a different approach and it will be best to be out in front of the crowd.

As Stan Salvigsen said: making negative comments about someone’s house is like telling them their kids are ugly. But the perspective toward inflation changes as we transition from working life to retirement. During the accumulation stage, many of our investments will benefit from inflation (i.e. appreciation). That is the case with real estate and stocks. During the distribution stage (retirement), we would prefer that inflation, particularly in the cost of living, remain stable so that the cash flow from a fixed income portfolio can maintain a stable lifestyle. Perception will be influencing reality as the Baby Boomer embraces the home stretch. Risk aversion and a demand for yield are very apparent in mutual fund flows. This is very likely to be the beginning of a trend rather than some contrary indicator for asset allocation.

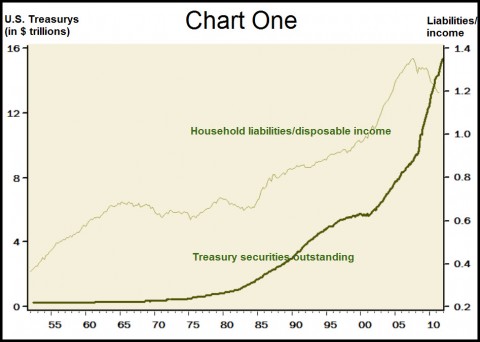

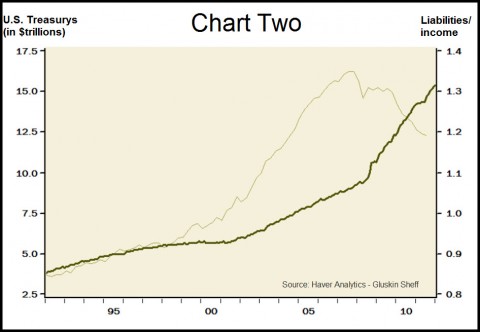

I have spent a tremendous amount of time trying to understand how the excesses created by the secular credit bubble will unwind. In the early stages (since 2007) of the new secular paradigm of credit collapse/contraction, public sector debt has expanded to make up for household sector credit contraction. The charts below depict household debt trends and indicate a peak, relative to disposable income, in 2007 (Chart One). However, with the economic contraction that began in late 2007, government debt goes parabolic and there seems to be no end in sight. Bob Farrell’s Rule #4 comes to mind: “Exponential rapidly rising or falling markets usually go further than you think, but they do not correct by going sideways.”

The largest component of household sector credit contraction has been default. Actual paying down of household debt has largely been offset by growth in student loans and to a lesser degree, a recent rebound in consumer installment debt that reflects confidence that the economy will once again achieve “escape velocity” and the old paradigm of debt fueled economic expansion will resume forthwith. Household balance sheets have reversed course but they have not been rebuilt yet.

No Banana Republic

Public sector debt first started ballooning in 2008 due to the bank bailout (TARP), Keynesian fiscal stimulus and programs to spur consumer spending. This was combined with lower tax revenues from a slower economy and an explosion in entitlement and safety net spending. The federal budget deficit has approached $1.5 trillion per year for the last 3 years and the national debt has increased by 43% (from $10.6 trillion to $15.2 trillion) just since the beginning of 2008. It is my contention that soon, household and public sector debt will be coming down together. The changes that are necessary to return to a level of indebtedness that can sustain a durable economic expansion will require substantial rebuilding of both household and government balance sheets. They have not been made yet, but it would be overly pessimistic to believe that, as a society, we will just drive the Thunderbird off the cliff into the realm of banana republic.

Powerful behavioral change will probably require some form of crisis, if history is any guide. For the 80th percentile, 57-year-old’s household, a combination of a recession accompanied by a resumption of the bear market in stocks and real estate would probably do the trick. Some comment is therefore in order pertaining to the potential changes in the political landscape. From a politician’s or central banker’s perspective, that is a doomsday scenario; and yet, the macroeconomic forces that are at work as the credit cycle unwinds make such a scenario highly likely. Witness Europe. Leaders in government and central banking across the developed world seem to be working in coordinated fashion to prevent the next recession from occurring by continuing to engage in behavior that stands in contrast to what the Baby Boomer household is moving inexorably closer to: frugality.

Political Process Responding

I usually get a laugh when I express my belief that, in this country, the political process is progressing as planned. This is, after all, still the best designed and greatest representative democracy ever. Yet, everyone seems to be focused on all the gridlock while all the changes that have taken place are largely going unrecognized. Consider that just since the 2010 elections, state and local budget deficits have been reduced by more than $350 billion. Most of this improvement is the result of a combination of spending cuts and tax increases. Local politics change quicker than national politics and they are a leading indicator. But our system of government was designed to accommodate change somewhat slowly at the federal level and that is probably a good thing. The federal election cycle is six years, and that is because Senators have six-year terms. We are half way through the current cycle. President Obama’s candidacy was in the bag before the downturn was recognized in early 2008, and by the time he took the oath of office, we were in the “Great Recession”. The momentum for expanding government was lost in the 2010 election and the national debate now firmly rests on balancing the budget and creating or preserving jobs.

By 2014, if we are lucky, politics will have made the journey away from polarization and back to the center where it needs to be during times of crisis. Then we will have the functionality to attack our problems forcefully and effectively. Even now, automatic budget cuts are legislated for 2013 and the Bush tax cuts and the Social Security tax cuts are both supposed to sunset at year end. Who knows? Maybe congress will see fit to allow meaningful budget reform to become law in the next few years. (Keep in mind that the congress is where legislation is created). We are clearly headed in that direction and a lot of votes remain to be cast. The dilemma is that we will be forced to pay the piper. A country united to save itself by rebuilding its balance sheet is not a model for growth and we are not the only country faced with a fiscal crisis. Most of the developed world is in as bad shape or worse. This will be a global phenomenon.

Monumental Challenges

The challenges facing us as investment strategists are monumental. This narrative is downright distasteful to those that subscribe to the muted growth forecast that is consensus. It also seems Pollyannaish to those that have legitimate fears that we are all going the way of Greece. But if we are in a depression, we still have to get out of bed each morning and put one foot in front of the other. In the present confusing circumstances, it continues to make sense to remain defensive and accept the idea that deflation is what awaits us around the corner, no matter how hard the central bankers around the world are fighting it. We have been through 31 year of disinflation and most of that was during an historic secular credit expansion. A period of modest deflation in consumer prices and more severe deflation in asset prices is a reasonable expectation if the changes outlined above are in store. We will need to stay the course in the fixed income markets and be prepared for better entry points in the stock and real estate markets.

(If you’d like to have these commentaries delivered free each day to your e-mail box, click here.)

I have the rule of 90 for my retirement – when I am 90 I can start thinking about retirement. I think just the thought of saving for retirement when costs for everything is rising – is enough to keep you from even starting or continuing to save.