[Our good friend Doug B., a financial advisor based in Boulder, CO, has done well for his clients by keeping them heavily weighted in bonds. In the essay below, he explains why he intends to stick with this strategy even though many of his peers expect a rebounding stock market to outperform fixed-incomes in the years ahead. For Baby Boomers in particular, the deflationary trend that buttresses Doug’s strategy holds stark implications. RA]

I was prompted to write this comment by the fact that, through Q3 of this year, the total return performance of long-term Treasury bonds has exceeded the performance of the stock market for the trailing 30-year period that began in 1981. I began my career as an “Account Executive” at Merrill Lynch in 1977 when brokers were leaving the business to drive taxicabs. It is a bit startling to think that the “benchmark risk-free long term asset” has won the race for practically the whole time.

I have had the opinion for some time that there are better risk-adjusted, total-return opportunities in the bond market than in the stock market. Consequently, I have favored bonds over stocks in my asset allocation recommendations to most clients — regardless of their risk tolerance or investment objective — since well before the stock market peaked during the Tech Bubble in 2000. For investors who have a more aggressive capital appreciation objective and higher risk tolerance, I have recommended bonds with very long maturities. For investors who are more inclined toward the stable-income and preservation-of-capital objectives that are more commonly attributed to fixed-income portfolios, I have recommended somewhat shorter maturities. In the final analysis, the prevailing economic and market conditions over the past 12 years have been extraordinarily volatile because of the extreme influence of credit bubbles. Locking in safe income in the bond market has been a great way to stay out of trouble. Recent events in the economy and the financial markets suggest that such an approach is still appropriate, looking out over an intermediate term investment horizon.

A Bond Benchmark

Bloomberg recently reported that long-term Treasury bonds have provided a greater total return than stocks for the last 30 years. The bond benchmark cited in the Bloomberg article appears to be Barclays US Treasury Long Bond Index, which captures the return for an aggregate of 20-year and longer Treasury coupon bonds. The benchmark for the stock market is the S&P 500 Index. The resulting 30-year returns are similar for bonds and stocks: 11.5% for long- term Treasury bonds and 10.8% for stocks. Over the last 12 years however, the S&P 500 has returned less than 1% per year, whereas the US Treasury Long Bond Index has returned over 9.5% per year.

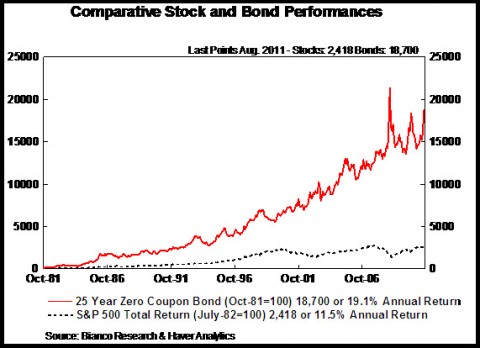

The chart below was compiled by Gary Shilling and it represents the performance achieved by owning and maintaining the duration of the 25-year Treasury Strip. It does a better job of capturing the performance of the very long end of the yield curve, which has provided a dramatically higher return (19.1% per year) vs. stocks (10.8% per year) over the last 30 years.

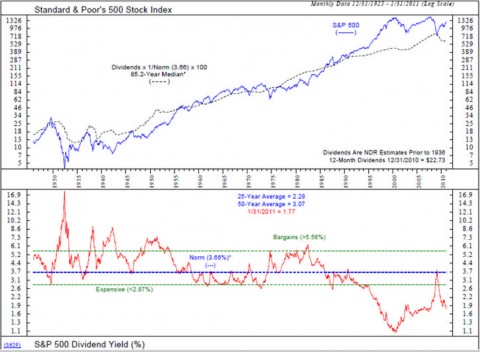

Much can be said about the difference in performance over the last 30 years between equities and long Treasuries. Bonds provided a higher return with much less risk. Nevertheless, conventional Wall Street wisdom is that, over the long term, stocks should outperform bonds because stocks do contain more risk as an asset class than bonds. Certainly, much of the out-performance in bonds in the trailing 30 years has occurred since the stock market ran out of steam in the early part of the last decade. Late in 1999 and early 2000, stocks achieved valuation levels that were spectacular by historic standards. The dividend yield on the S&P 500 hit a low of 1.1% (see attachment) and the trailing 12-month reported P/E Ratio hit 35 times. Neither of these levels was in the same zip code as previous secular peaks. Since then, stocks have delivered negative price performance and the total return — less than 1% per year — is positive only because of dividends. On the other hand, Core CPI inflation, which is the primary determinant of long-term Treasury bond yields, has been declining continually since 1981 and has remained very consistently 2% to 3% below the long -bond yield (see chart below). Rarely have long-term Treasury Bonds been expensive relative to this primary valuation benchmark, and only for brief periods.

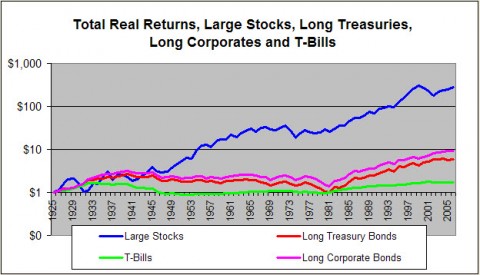

When presented with the track record, many pundits immediately conclude that 30 years of underperformance by stocks compared to bonds is a reason to expect equity market performance to improve. I have displayed the ubiquitous Ibbotson Chart (above), which I think is a party trick, but it has formed the graphic embodiment of the general Wall Street doctrine that “over the long haul, stocks outperform.” In reality, 11% per year for 30 years is not bad for anything historically, be it stocks, bonds or modern art. In the case of stocks, it is especially stunning considering that stock prices were flat for the last 12 of the latest 30 year period. The fact that stock prices went parabolic from 1982 to 2000 convinced most investors that a linear reality existed, much as the belief in rising home prices became doctrine during the real estate bubble.

Here’s a relevant note from Merrill Lynch legend Bob Farrell, dated August 3, 2001:

A Secular Inflection Point?

“Change of a long term or secular nature is usually gradual enough that it is obscured by the noise caused by short-term volatility. By the time secular trends are even acknowledged by the majority, they are generally obvious and mature. In the early stages of a new secular paradigm, therefore, most are conditioned to hear only the short-term noise they have been conditioned to respond to by the prior existing secular condition. Moreover, in a shift of secular or long term significance, the markets will be adapting to a new set of rules while most market participants will be still playing by the old rules.”

paradigm \ n\ 1: EXAMPLE, PATTERN; esp: an outstandingly clear or typical example or archetype.

We appear to have entered the process of mean reversion, and we must be reminded that mean reversion requires two extremes. It is not inconceivable that before the mean reversion is complete, stocks and bonds will display 30 year returns that are closer to 5% or 6%, or lower. In the case of stocks, a return to an appropriate mean over the intermediate term would require a sizable drop in prices. Coincidentally, so would a return to levels of valuation commensurate with historic bear market extremes. The dividend yield today on the S&P 500 is 2.1%. Something north of 5.5% has prevailed at normal bear market extremes in the past 86 years that are contained in the Ibbotson data (see S&P yield chart, above). It would take much more than a 50% drop in the market to bring the dividend yield down to bear market extremes. A much larger decline than that would be required over the intermediate term in order to revert the 30-year return back to 6%, which would represent a low end extreme.

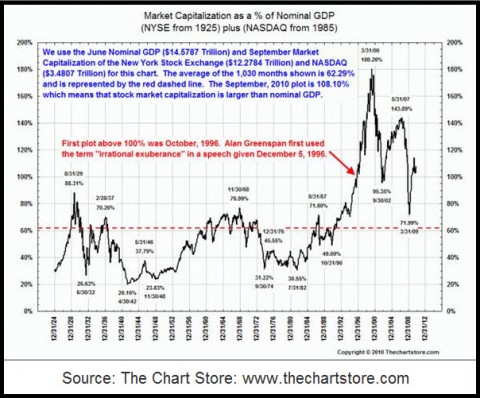

This second chart from Bob Farrell displays one view of stock market valuation:

Quoting Farrell: “A return to the mean includes two extremes, not just one. One measure of valuation we consider valid is stock market capitalization as a percent of GDP. From the 1920s to the 1990s, it only went over 80% once (1929) but since has been as high as 180% in 2000 and as low as 72% in 2008. The current level of 110% is still high historically and only at a mid-level if you think history begins in the 1990s (see chart).”

And that leads me to thoughts on the “C” Wave. According to Bob Farrell, bear markets occur in three waves; A down, B up and finally C down. If we are headed for recession, then this latest decline phase is the beginning of the “C” Wave. In hindsight, the peak of the secular credit expansion that began at the conclusion of the Great Depression occurred in 2007 with the demise of the housing bubble. The Great Bull Market may have ended in 2000 (with Intel at $76), but the Bear Market did not begin until late 2007. That was the true secular inflection point. What happened in between was some kind of screwed up meat grinder. The “A” Wave began at the all-time highs on the S&P500 in October 2007 at 1576 and ended in March 2009 at 667. That was also the start of the “B” Wave that presumably ended in May 2011 at 1370, ushering in the current decline phase.

See-Saw Markets

Bull and bear markets display see-saw characteristics and seem to be a reflection of human nature which, generally speaking, does not change. Bob Farrell alluded to it in Rule#8: Bear markets have three stages – sharp down – reflexive rebound – a drawn-out fundamental downtrend. Dick Stoken took it a bit further:

“Because human psychology is slow to change, a broad economic move usually occurs in three stages. The first stage begins when some unexpected event shatters an overdone psychological environment. Yet, while some people respond immediately to this new lesson, most people, as they find it outside their past experience, do not believe it. They need more evidence- that is, a second stage. Typically, the majority become convinced during the second stage and therefore the psychological background changes. People begin to act differently, and their behavior soon affects the performance of the economy (my italics).”

Stoken’s Behavioral Model

Dick describes the “A” wave and the “C” Wave as impulse waves in which market participants are acting rationally in the face of disappointing fundamentals. The disbelief that occurs in the second stage allows for the “B” Wave, which is counter-trend. Earlier, I quoted the paragraph written in 2001 by Bob Farrell pertaining to secular (long term) change because it deserves to be pinned to the wall right next to Market Rules to Remember. He explains magnificently what the psychology of the “B” Wave is: disorientation. The “C” Wave of a secular bear market or a new paradigm occurs when investors become aware that a “new set of rules” is operative.

So what about the bond market? That bull market probably has a few years to go. For some reason, the popular focus is still on inflation and most market participants do not even know how to spell deflation. This is after the collapse in housing prices and a stock market that is lower in price than it was 12 years ago. Still, the only thing that market strategists seem to agree on is that danger lurks at the long end of the yield curve. (It is tough to lose money with that kind of sentiment.) Yes, 30-year Treasury bonds yields are down to 3%, but if they go to 2% over the near term, the total return will be much greater than the coupon. After all, we started 2011 at 4.33% and the total return on the 30 year coupon bond is 30% year to date. The long Treasury Strip is up 54%. The decline in rates can continue if Core CPI inflation continues to melt and the Fed stays on hold at 0% at the short end of the curve. Two weeks ago, the Fed lowered their forecast for GDP growth, employment and inflation through 2013. It is widely assumed that their explicit promise to hold rates at 0% through mid-2013 will have to be extended well into 2014. If we are heading into recession, Core CPI is likely to go negative (that’s right; the “D” word).

Tax-Frees Yielding 7%!

In addition to the potential in long-term Treasury bonds, Closed End Municipal Bond Funds are yielding close to 7%, tax free. Closed End Build America Bond Funds yield over 7.5% and sell at steep discounts to their net asset value and the underlying bonds have excellent call protection. Compare that to soap or hamburgers with a 3% dividend yield.

For the last four years since the bear market began, the investing public has been hoping for, and policy makers have been pushing for, a return to the old paradigm. That is to say, through a desire to bring back the good old days, there has been general acceptance of trying to solve the credit crisis and attendant economic and financial malaise with more debt and fiscal and monetary stimulus. After all, it did work (in some combination) in pulling us out of each of the recessions during the post WWII period up until now. But here we are-pushing on a string, engaged in a political revolution relative to deficit spending and the Fed is holding a water pistol. Repeated attempts to spur consumer spending through temporary policies like “cash for clunkers” and mortgage modification have been ineffective. So have other more general fiscal measures like reducing payroll taxes and extending unemployment benefits. The fact that households understand that they are over-indebted has resulted in conventional policy stimulus being rejected. In Europe, efforts to save the over-indebted peripheral countries have been similarly futile. It is becoming much more obvious that the easy road is not the one that leads to the solution. It will be a slower and longer road in every respect that will lead to the next expansion. We are not going to grow our way out of this.

Here in the New Secular Paradigm, we are just now learning that we need to play by a new set of rules. We apparently need to eliminate debt in a big way. We must return to levels of debt relative to GDP and household income that can be the base of the next secular economic expansion. Escape velocity cannot be achieved until debt levels mean-revert too. It will be the moral (and economic) equivalent of war. The compound interest table is a far more formidable foe than the Third Reich and we will be facing a federal government debt exceeding $18 trillion in the next few years. This is in addition to extreme levels of household and state and local government debt.

Baby Boomers’ Grim Reality

By a particularly evil twist of fate, the developed world’s Baby Boomers arrived on the doorstep of retirement in 2007 with a household debt/disposable income ratio exceeding 130%. That compares to a ratio of less than 30% at the end of WWII when they were being conceived. Let’s face it, we could not have timed the real estate mania any worse. Theoretically, we Boomers should be flush as we approach our 60s, but look around. The 80th percentile 57 year old household owes more in mortgage debt on their home(s) than they have in their 401Ks. So, going forward, the business of America is debt reduction. There is not, under any reasonable forecast, a growth outlook in the developed world that could trump the debt destruction that will be required for the credit collapse to come to completion. In the absence of growth, debt is eliminated via some combination of austerity and default.

The U.S. savings rate dropped from 5.3% to 3.6% in the three months ending September 2011, as the wealthy continued to save or pay down debt and the not-so-wealthy were buying gas and groceries on credit. The Supercommittee in Congress has decided to punt. Their daunting responsibility was to narrow the budget deficit through smoke, mirrors, increased taxes and cuts in entitlement spending. The politics evolved at lightning speed, leaving us to scratch our heads. But probably not for long. The winds of change are clearly blowing. It is reasonable to believe that political trends are also undergoing secular change. Why should we doubt that the American Democracy will defeat the compound interest table? We managed to prevail over every other dire threat in our history and preserve the Union. Here too, conventional wisdom is suffering from linear thinking.

What Can We Do Right?

So, what can do right? How can we avoid the hardship? How can growth return to levels where the debt can be serviced, causing inflation to increase and the Fed to tighten? I have been presented with several possibilities that come from people who are thoughtfully aware that a credit collapse is occurring. The most popular expectation is for a decoupling from the developed countries by the emerging markets. Countries like China have low debt and their enormous population is characterized by low consumer spending and high savings rates. Perhaps they can “emerge” into a level of domestic consumption that buoys the global economy even if they experience less export demand from the developed world. We can then continue to sell them more soap and hamburgers. Then there is the “killer app.” This refers most commonly to some invention like the steam engine or the Internet, but it could also be a geopolitical event — i.e., globalization or the end of a war (or two). It has to do with some unknown yet spectacular productivity enhancement that will drive the global economy. It better be really big and quick. Hope springs eternal.

I find it far more intellectually appealing to accept that we are simply overdue for a bit of winter and we need to deal with it. After all, everything that we have observed so far about the universe is cyclical. And that just brings me right back to Bob Farrell’s Market Rules to Remember. Rule #2: “Excesses in one direction will lead to an opposite excess in the other direction” is why getting back to normal after a parabolic move requires a second excess before settling back to the mean. And yet, this is the last thing that conventional thinking typically allows for. At worst, periods of excess are expected to hold their gains (or losses) until the fundamentals catch up. More often, periods of excess are interpreted as the arrival of a “new era” in which past cyclicality has been defeated so history no longer applies.

Yields Uncorrelated

Fortunately, during the last 12 years of flat prices, the yield on the S&P 500 has doubled from 1.1% to 2.1%, catching up exclusively because dividends have gone up. But prior to 1995, the S&P 500 never traded richer than a 2.5% yield at any market peak. Current conventional thinking is either; dividend yield is an outdated valuation metric or, more popularly, 2.1% ain’t bad, considering that the 10-year Treasury only pays 2%. In fact, there is no correlation between Treasury note yields and dividend yield on the S&P 500. From 1932 through 1955, the yield on stocks was consistently above 6% while the 10-year Treasury note yield held below 2%. And yet, the pundits insist that the market is cheap today for some reason.

Returning to the issue that both stocks and bonds have achieved 10%+ total return performance annualized for the last 30 years, one has to wonder what an appropriate mean reversion target ought to be. Consider that real economic growth in the U.S. averaged less than 3.5% per year since late 1981. As the Ibbotson chart shows, core inflation has exceeded 5% in only three of the last 30 years. Further complicating the issue is that, since we have only recently (2007) entered into our credit collapse, real GDP growth for the next decade is bound to be much lower than 3.5%. Core inflation, which has been making its way down from over 13% in 1981 to less than 2% today, is likely to stick pretty close to zero for the next decade, if Japan’s experience is any guide. Low, single-digit returns (5% to 6%) may be the mean that we will be reverting to. Even during the credit expansion that was in force from the depths of the Great Depression to the peak of the housing bubble, annual total returns were around 9%. As David Rosenberg is fond of saying, “You do the math.”

Reverting to the Mean

There are many possible scenarios for mean reversion of stock-market returns, but consider this: For the last 10 years of the current 30-year period, we have been subtracting the performance of 1972 through 1981 while we added the performance of 2002 through 2011. Both periods were remarkably flat (no price appreciation, just dividends). Going forward, we will be dropping the period starting in 1982. In 1982, the S&P 500 started the year at 123 and the dividend yield was 5.64%. Ten years later at the end of 1991, it was at 417, up 340% in price. Dividends almost doubled, but the yield had dropped to 2.91% due to the higher index price. The annualized return was more than 17.6% for those 10 years. If the market dropped in half (i.e., to 620 on the S&P 500) over the next couple of years, we would add negative 50% for 2012 and 2013 and drop off the 50% positive return from 1982 through 1983. That would lop off close to 3% from the 30-year annualized rate, to 7.2%. That would get close to the proposed mean. It would not qualify as an opposite extreme because that would require a number on the other side of 6%. If dividends stay at $26, the market will be yielding 4.2%. Nothing particularly extreme there either, but at least then, we would be getting somewhere.

***

(If you’d like to have Rick’s Picks commentary delivered free each day to your e-mail box, click here.)

D.O.,

It is nice to know how you really feel.

When people come to the bank to withdraw, there will never be a problem. If it is expedient, then the bank will be closed, but the people will always get their money. Why? Because, there is no problem in creating paper. And, if as you say, there can someday be such a problem, then what the government will do is offer digital withdrawal. If this offer is not welcomed, then it can offer same digital option plus 5%. Not enough? It can offer same plus 100%, or 1000%. There is no limit.

Gold $1500? As a correction? Why not. I would not argue against that. But to say that the gold will come down to $1500 to stay is to assume that there are actually honest people in the governments. Very naive, if you ask me. All claims on purchasing power must equal all goods and services at all times. All gold, too, must equal to all goods and services at all times. From here it can be deducted that all gold must also equal all paper and digital claims. This means that at, say, $2000, the POG is unreal, too low. Too many claims do exist.

RA,

(I like that, “RA”, sounds like “RA, the one and only”, no offense) have said above, that he has a trouble to see who would have the money to pay $50,000 for an ounce. The answer is simple, maybe not RA. But many people have that and more. Secondly, RA, do you really believe you are say, eight times richer that your parents were? They likely had one $10,000 car. You likely have two, $40,000 cars. Your dad could have asked the same question, “who would have $40,000 to buy such an expensive car!” Yet, not only you do have that, you also had another $40,000 to buy a second one. Magic of inflation. In original definition, inflation is an increase in quantity of money. Meaning that the government will see to it, that people do have $50,000 to exchange for an ounce of gold.

Seawolf,

I refer to “printed” money as stolen, for clarity.

Here is my explanation:

If I come to your wife and say you own me some money, and she pays me for it by giving me your car, would you not say I stole it?

When I lied, I have produced a fraudulent claim, and when I took the car in exchange for my lie, I stole it.

Money is a claim on goods and services. Yes, one can “print” counterfeit claims, or even create them digitally, but they are still nothing, until an exchange is made, and something real had been gotten for it. Printing or digitally creating is only a deception, a lie that these claims are real, but once FED buys something for them, it steals from everyone who holds his purchasing power in paper or digital claims.

The FED has many layers of deception, this is because the Congress wants to be protected from the heinous crime that it commits through the FED. One of this layers is the belief that the FED is a private bank. But the act of printing money from the air, is no less a deception. It is only a lie to conceal that there is actually a theft going on.

Most people believe that the government has or earns money. Fewer believe that the government prints or digitally creates money. Even fewer people know that that is a nonsense, that the government only lies that it can create something out of thin air, instead, it has to lie in order to steal.